Seeing the Forest and the Trees

We need to change from a timber priority to a priority of forest resilience, John Innes – Forest Renewal B.C. chair in forest management (in The Current, Sept 26, CBC radio).

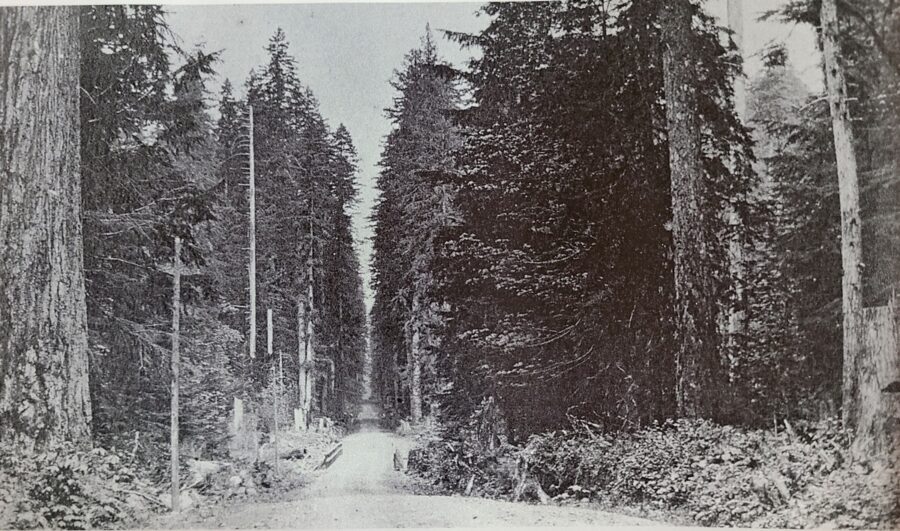

Photo above: The Black Creek bridge on what is now the Island Highway between Courtenay and Campbell River, 1918. Davey Janes recalled that “it was like looking down a hole in the timber”. From: Island Timber by Richard Mackie

Giant trees have an aura. When I walked through the “Old Growth Loop” at Elk Falls Park, I had the same feeling I sometimes get walking through an art gallery. You have to tilt your head way back to find the tops of the trees, then straightening your gaze, you are faced with the roughly textured and impossibly thick bark of their massive trunks. They have a palpable presence. The experience of seeing something so precious, rare, or sacred, affects me emotionally. At the same time, being on Vancouver Island, I was aware that just outside this small loop, evidence of logging prevails.

I wonder if industrial logging hadn’t ever happened, would I still see feel the same sense of awe with these giants. Afterall, they wouldn’t be so rare. If it was 150 years ago maybe I would have felt more like they were beasts to be conquered. Old black and white photos of the Vancouver Island highway show a narrow dirt trail like a tentative crease through an impenetrable forest. At this time, on the whole, people felt that subduing the chaotic landscape was the “foundation for future profit”. These trees would have been seen as a barrier to creating homesteads and growing food; something to overcome. At that time, the thought of ever cutting all these trees down seemed like an impossibility. Now it seems like an impossibility that any old growth are still standing.

In the early 20th century, these trees, particularly the Douglas fir, would start to be seen as not only obstacles, but as a means to make money – a source of opportunity, problem solving and enterprise. Livelihoods for entire communities ensued, along with new identities as loggers and millworkers. (My father in law was a logging truck driver in Nimpkish). The unsavory smell of pulp mills was a small price to pay for lifelong jobs, steady income, pensions as well as a sense of purpose and identity.

The fact that trees were so lucrative was not necessarily good for the tree. I remember as a six year old, driving to Gold River with my parents and seeing the strange patchwork of squares on the hills in the distance and asking what they were. I don’t remember a satisfactory answer, maybe just having moved from southern Ontario, my parents were not sure themselves. Later on, as a treeplanter I became intimately familiar with clear cuts, seeing with my own eyes the effects of logging, especially on Vancouver Island. From remote logging roads and helicopters whole mountains and hills were denuded of trees except for a cute little tuft of trees on top, as if this powerful industry was poking fun at nature. I saw many creeks and streams choked with debris and slash and as we often see around us, rivers abundant with gravel that has washed downstream, loosened by logging activity.

Today, as our fore bearers couldn’t imagine (well a few of them did), not much of the original forest is still standing (the amount and where it is – subalpine, bogs or productive forests – is a bit controversial). Logging has gotten so efficient, it just takes one person to log an entire block of second growth trees using a feller buncher. (It’s quite something to watch: one person alone operating a large whining machine that grabs a tree with it’s pinchers, saws it off with a built in blade and then places it on a neat pile.) Also, logging companies have become owned by just a few large multinational corporations, where lines on maps are drawn by people in a distant office, focused on profit maximization to satisfy stockholders – people who haven’t stepped on the land themselves. What we’ve ended up with is a monoculture of forests, tightly spaced with no undergrowth, susceptible to fire and disease or pests. Foresters have been warning the government for years about the dangers of these logging practices. (As far back as the 1860s, George Marsh wrote in “Man and Nature”: “We have felled forest enough” and “Earth is fast becoming an unfit home for its noblest inhabitant”.)

So now when you see old growth trees in Campbell River, Port Renfrew or on the postage stamp size piece of land called Cathedral Grove, on the way to Port Alberni, it’s not likely they were protected for the sake of biodiversity – you need much larger swaths of land for that (like Clayoquot Sound). These trees remind the general public of what used to be all around us. I’m not sure what our response is supposed to be. Inspired by beauty? Educated? Mournful? I think it is a big question mark. I think we are just supposed to be left wondering, maybe how and then why, are just these few old trees left and replaced by less majestic forests.

We can be thankful for the wood and pulp which provided materials (including cellulose, which is in everything, even ice cream) for our houses and communities and improved all our lives. The arteries of logging roads have allowed us to access wilderness for camping, mountain biking and fishing. Money from forestry has paid for community programs and municipal infrastructure – whole cities wouldn’t have existed without it. Many peoples’ livelihoods have depended on it. But as with most things involving human ingenuity, enterprise and ambition (and not necessarily thinking ahead about the long term health of ecosystems), there has been a tall price to pay. We reaped all these benefits but in time, set in motion a monstrous industry. It happened before we had a chance to poke our heads above the trees and look beyond. Before we had a chance to reflect, wonder or learn if this was the right thing to do and the best way to do it.

The way forests and fire have been managed in B.C. over the last 100 years has increased the scale and intensity of current wildfires and decreased landscape resilience. In 2017, 2018 and 2021, B.C. experienced it’s three largest wildfire seasons in 102 years of recording fire, climate and weather history, affecting 3.4 million hectares of land. If the way forests and fire are managed doesn’t change, B.C. will face many more catastrophic wildfire seasons. From Forest and Fire Management in B.C.: Toward Landscape Resilience, a report by the BC Forest Practices Board, June 2023 – quoted in Watershed Sentinel magazine. I think they are a little late in admitting this!

To learn more about the history of logging and forests on Vancouver Island:

Timber History by Robert Mackie – a fascinating history of the “glory days of logging” on Vancouver Island. Full of amazing photos.

Now You’re Logging by Bus Griffiths – a graphic novel published in 1978 that details the life and work of two (very buff) loggers – paintings by Bus Griffiths are in the Courtenay Museum and also the Fanny Bay Community Hall. I found this book in a second hand book store.

Greenwood by Michael Christie (fiction but shows interesting perspectives from both environmentalists and logging magnates).

And one of my faves: Ross Reid @nerdyaboutnature (Instagram) and his videos are also on his Youtube channel HERE. Based in Ucluelet he shares fun facts about nature and specifically about trees, forests and sustainable logging.