How Birds Give Us a Sense of Wonder

“There is clearly no single bird way of being but rather a staggering array of species with different looks and lifestyles. In every respect, in plumage, form, song, flight, niche, and behavior, birds vary. It’s what we love about them”. The Bird Way, by Jennifer Ackerman

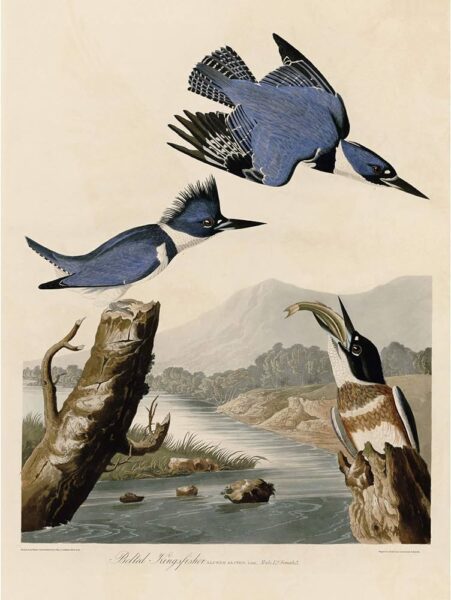

One of the most precious gifts I received as a child was a large picture book of birds painted by the 19th century ornithologist/artist, James Audubon. It was from my grandparents in Ontario, who wanted to encourage my love of drawing. I was already fascinated by birds, so this book was a goldmine. I would spend hours with my black hardbound sketchbook, pencils and set of Prismacolour pencil crayons, drawing the different colours, shapes and forms of Audubon’s birds. I practiced capturing the softness of feathers, measuring the proportions of the tertiary and secondary wing feathers and started to recognize the categories of birds; nimble perching birds, birds of prey, colourful ducks and then the fantastical tropical birds like parrots or Birds of Paradise. To this day, I can recognize and name some of these different birds.

At the time I imagined my future as an artist sitting behind a camouflage blind in a field, observing and painting them in exact detail. I was disappointed to learn much later that Audubon actually shot the birds he wanted to paint, though he spent real effort trying to set them up in scenes to look like they were active in their natural habitat. It explains why larger birds would be in strange, contorted positions – it was so he could fit the whole bird on the page.

This early education about birds came to life when my little sister and I found a baby starling while playing outside and were allowed to keep it. We put it in a shoebox and fed it egg with an eyedropper and called it “April” after the month we found it in. (We also later found a “May” but she didn’t survive.) When April got bigger, he would sit on our shoulder while we were watching television and angrily peck at your neck if you moved. It was so exciting to get this intimate visual and tactile experience of a bird. During that summer when we took April outside, he started to learn to fly, a little farther each time, sometimes totally freaking out a passerby by trying to land on their shoulder. He always came back until finally one day he didn’t. Hopefully he went on to fully realize his life as a starling. (Any gender identity was purely a guess).

I recently read “The Bird Way” by Jennifer Ackerman which is full of many different examples of birds living in every which way you can imagine. The variety of mating rituals, habits and behaviors is truly stunning; from the artistic displays of the bower birds, to the flying stunts of hummingbirds, to the vocal mimicry of the lyrebird – some of it sounds so crazy it seems made up.

This whole idea that birds are stupid; “bird brains” because they have such small brains (to keep their weight down so they can fly), is actually false. The size of the brain doesn’t matter, because in birds’ brains the neurons are more densely packed. And actually their brains aren’t actually all that tiny in proportion to their body size.

Birds have been known to fashion tools and use them, they are social and can recognize faces and can stash food in hundreds of different places and remember when and where they stashed it. They have a complicated social organization – think “pecking order”. They also have an uncanny sense of direction, partly because they can read the position of the sun but also even more impressive, sense the magnetic field of the earth. Corvids (ravens, crows, jays) are particularly intelligent and even love to play. They will stick their head in an empty flowerpot and “caw” just to hear the echo. The more you learn about other animal’s abilities, the more it makes you feel, as an individual human, somewhat unimpressive.

Recently when I was camping with friends at the Croteau Lake group site at Strathcona Park I started to recognize a particular Whiskey Jack (or gray jay) hanging out with a more fluffy, bedraggled version of herself that I guessed was her offspring. I think she was showing him the ropes, as she would sit on a branch and watch while the fluffy one would come and try to steal food. At one point the older one, to show her protegee how it is done, stole an entire tea bag from me, with the tag dangling off it, and flew to the top of a tree. The jays are so tame in Strathcona Park that I imagine if you stayed there for awhile, that over time you could get to know the individuals. I did start to wonder if they were recognizing me, just the way they look you in the eye and then also come back again. Maybe because I was paying attention, one of them landed on my foot when I was sitting on a chair, though I wasn’t eating anything and refused to feed them – it just felt like she was checking me out.

I’ve been making more of an effort lately to recognize birds and their songs in my neighborhood (with help from the Merlin bird app), like the White-crowned Sparrow, Bewick’s wren, Swainson’s Thrush or the Black-headed Grosbeak which has very impressive vocals. They were all here in the spring, but now that it is fall, they have gone to sing their songs somewhere else. One time this year I saw a resident robin who I’m pretty sure was panting in the May heat wave. I put out a dog bowl of water for him, which I saw him drinking from later. Hummingbirds have also been a constant presence in the garden, getting territorial with each other and emitting iridescent bright flashes of colour in the sun.

Birds are our companions, always there to remind of us of parallel non-human lives that exist independent of us. Imagine a beach without seabirds or a pond without ducks, a lake without loons, a park without pigeons or a sky without eagles. We expect birds to always be there in our periphery, living out their lives; parenting, having love affairs, hunting or perfecting their songs. They are a regular background reminder that there are so many different realities existing right before our eyes that have nothing to do with current events, social problems or the price of groceries. Paying attention to this (maybe by just noticing, drawing, or having a bird feeder), we may realize how much humans are not center, but just a part of a larger earth community. I think with this awareness we have a chance to have a more reciprocal relationship with nature, fostering the sense of wonderment we naturally had as children. If we find an abandoned nest and marvel at its amazing craftsmanship or find a robin’s egg and admire the delicacy and colour, we have received a gift – a peek into a whole other world.

“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

Aldo Leopold, 1949